Tree Climbing Lions

Tree-Climbing Lions: Africa’s Most Elusive Big Cat Behaviour

When we picture lions, we see them lounging in golden grass, stalking across the savannah, or roaring from rocky outcrops. But in certain parts of East Africa, these iconic predators are defying expectations—by climbing trees. Welcome to the world of tree-climbing lions, a rare and fascinating phenomenon that turns the traditional image of the “King of the Jungle” on its head.

The Rare and Mysterious Behaviour of Tree-Climbing Lions

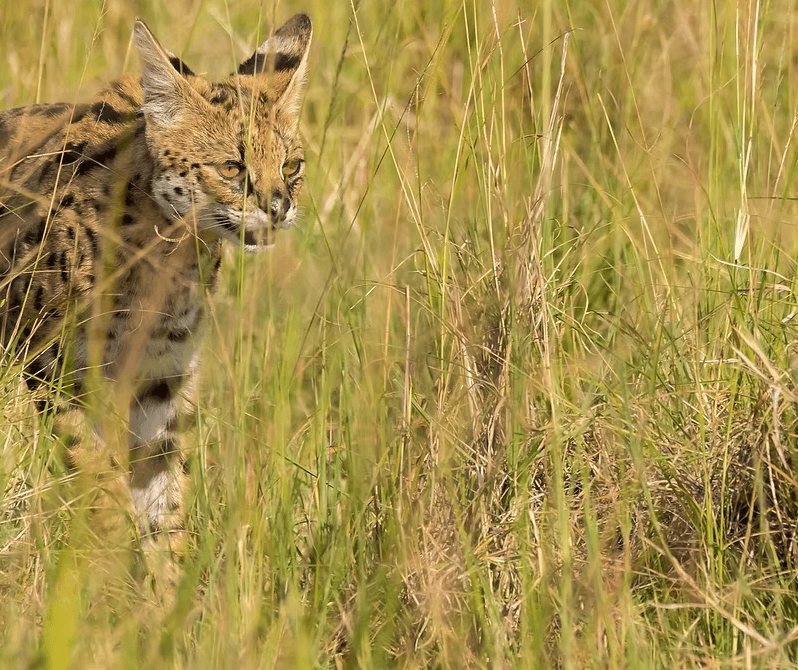

Not All Lions Climb Trees

Most lions across Africa remain firmly on the ground. However, a small and unique population in Uganda and Tanzania regularly climbs trees—and not just for a moment. These lions rest, nap, and observe their surroundings from the branches of fig and acacia trees for hours at a time.

The reasons behind this behaviour remain the subject of scientific curiosity. Researchers have proposed several theories:

-

Avoiding the heat by catching cool breezes higher off the ground.

-

Escaping insects such as tsetse flies and ants.

-

Gaining better visibility of potential prey or threats.

-

Learning through social behaviour, passed down by mothers to cubs.

This rare and mysterious behaviour sets tree-climbing lions apart from the rest of Africa’s lion population—and makes them one of the most sought-after safari sightings.

Incredible Photo Opportunities You Won’t Want to Miss

Lions That Pose Like Leopards

Imagine a muscular lion draped across a fig tree branch, its tail swinging lazily and eyes scanning the savannah. The visual contrast between this powerful predator and the delicate canopy of a tree is both striking and surreal.

These moments offer incredible photo opportunities unlike any other safari experience. Whether you’re a seasoned wildlife photographer or a first-time visitor with a smartphone, capturing this behaviour is a true highlight.

Because the lions often stay in the trees for long periods, you have ample time to:

-

Frame the perfect shot.

-

Observe their body language.

-

Capture rare interaction between lions on branches.

Best Photography Tips:

-

Use a telephoto lens for clearer shots from your vehicle.

-

Visit during the early morning or late afternoon for the best light.

-

Stay patient—these lions love to lounge for hours in one spot.

Only Found in Two Main Places in Africa

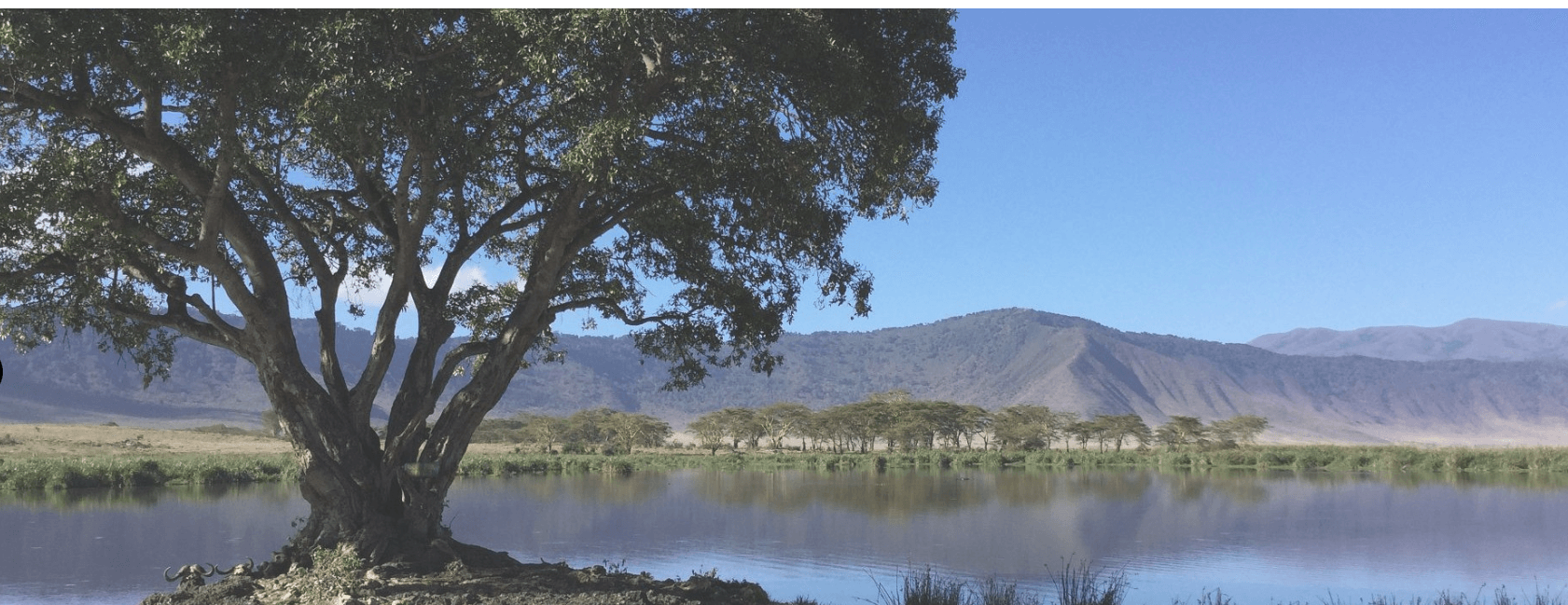

Ishasha Sector, Queen Elizabeth National Park – Uganda

The Ishasha Sector in southwestern Uganda is the most famous and reliable place to spot tree-climbing lions. Part of Queen Elizabeth National Park, this remote region features vast open plains dotted with flat-top fig trees—perfect for lounging lions.

The local lion prides have adopted tree-climbing as a cultural trait, making sightings here more predictable than anywhere else. Expert guides know exactly which trees to watch, increasing your chances of a successful encounter.

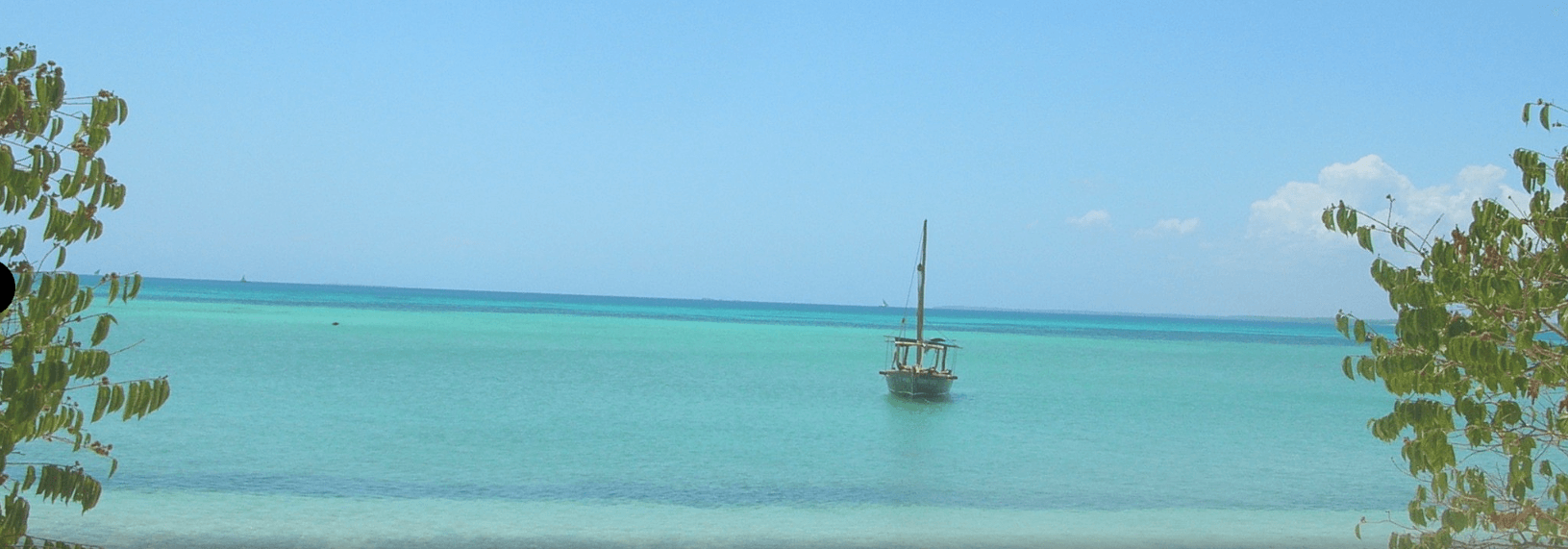

Lake Manyara National Park – Tanzania

Lake Manyara, nestled between Tarangire and Ngorongoro, is another hotspot. The park’s scenic beauty, dense forests, and alkaline lake make it a biodiverse haven, and the lions here have also been observed climbing trees.

However, sightings in Lake Manyara are less consistent compared to Ishasha, making it more of a lucky bonus than a guaranteed highlight.

Interesting Fact: While lions can technically climb trees anywhere, habitual tree-climbing lions are only consistently found in Ishasha and Lake Manyara.

Elusive, Exclusive, and Unexpected Safari Experience

A Surprise That Never Fails to Amaze

Even in known hotspots, tree-climbing lions are not guaranteed—making a sighting feel even more exclusive and unexpected. This element of surprise adds a thrilling edge to any safari.

When your guide points out a lion reclining in the branches, the moment feels truly magical and rare. Most travellers don’t believe it until they see it with their own eyes.

This elusiveness adds value to the experience. Unlike more common sightings such as elephants or antelopes, tree-climbing lions offer something few travellers get to witness, making your safari truly stand out.

Behaviour Passed Down Generationally

A Learned Tradition Among Lions

Tree-climbing is not instinctive for lions—it’s a learned behaviour. Cubs in Ishasha and Lake Manyara learn by watching and mimicking their mothers, who have perfected the technique over generations.

This means the behaviour is culturally specific to certain lion populations, not widespread across the species. Like tool use in chimpanzees or song patterns in whales, it highlights the complex social learning among wildlife.

In areas where tree-climbing is common, new generations continue the tradition. But in other lion habitats, lions rarely or never climb, simply because they haven’t learned to.

Remarkable Insight: “In Ishasha, climbing isn’t just survival—it’s tradition passed from mother to cub.”

Why This Matters for Conservation

Protecting Unique Wildlife Behaviours

Conserving tree-climbing lions isn’t just about saving lions—it’s about preserving unique wildlife behaviours that may disappear if these populations are not protected.

Conservation Challenges:

-

Habitat encroachment from agriculture and development.

-

Poaching and human-wildlife conflict near park boundaries.

-

Climate change impacting prey distribution and tree cover.

By promoting eco-tourism in places like Ishasha, travellers directly support:

-

Community-based conservation efforts.

-

Anti-poaching patrols and wildlife monitoring.

-

Education and healthcare projects for local families.

Your Role in Conservation

Every time you book a safari to see these lions, you contribute to:

-

Sustainable wildlife tourism.

-

Increased protection of habitats and wildlife corridors.

-

Revenue sharing that benefits local communities and incentivises conservation.

Meaningful Travel: Your visit isn’t just a thrill—it’s a step toward safeguarding one of Africa’s rarest animal behaviours.

Look Up, and Be Amazed

Tree-climbing lions are one of Africa’s most bizarre, beautiful, and baffling wonders. They challenge our assumptions about lion behaviour and offer a safari experience unlike any other.

From their mysterious habits to their majestic poses above the plains, these lions embody the unexpected magic of Africa. And with only two main places in the world to see them—Ishasha in Uganda and Lake Manyara in Tanzania—the experience is as exclusive as it gets.

So next time you’re on safari, don’t just look around—look up. You just might find a lion where you least expect it.

FAQs About Tree-Climbing Lions

🔹 Why do some lions climb trees?

Likely to escape heat, insects, or for better views. In Ishasha and Lake Manyara, it’s learned and passed down.

🔹 Where is the best place to see them?

Ishasha Sector in Queen Elizabeth National Park, Uganda offers the most reliable sightings.

🔹 Are they a different species?

No. Tree-climbing lions are ordinary African lions displaying extraordinary learned behaviour.

🔹 Is it easy to photograph them?

Yes, with the right guide and patience. Early morning or late afternoon is best for lighting.